Git and GitHub for Word users

Many people working in academic libraries and university presses find themselves adjacent to both tech and the academic humanities. In particular, they may work closely with a team that uses Git and GitHub to manage projects that include text in English or another human language.

While Git and GitHub can seem quite alien to teams of writers and editors, if they’ve used Microsoft Word or Google Docs for any length of time, they have a way in. Common ways of using Word and Docs in the humanities bear a striking resemblance to Git concepts, and they can serve as a frame of reference for Git and GitHub concepts.

Git or GitHub?

What is the difference between Git and GitHub?

Git is an old-school command-line program for version control that programmers use by typing text commands into a terminal window. It also works across computers and servers, allowing for close collaboration. It is free and open source.

GitHub is a cloud storage service that lets programmers use Git commands and concepts to store, share, track, plan, and review code. It is owned by Microsoft and has some free and some paid features.

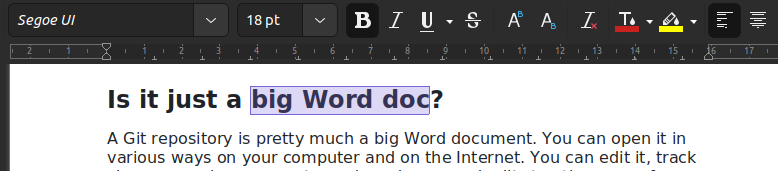

Is it just a big Word doc?

A Git repository is a big piece of text, and GitHub is a place for managing text (okay, code, but code is just text). So in an abstract way, yes, what you see on GitHub is something like a Word doc.

GitHub offers many features that are analogous to features in Word. With both Word and GitHub, you can open your work in various ways on your computer and on the Internet. You can edit it, track changes, make comments, and send proposed edits to other users for them to approve, reject, or counter. You can see a version history and revert to earlier versions.

How GitHub treats files

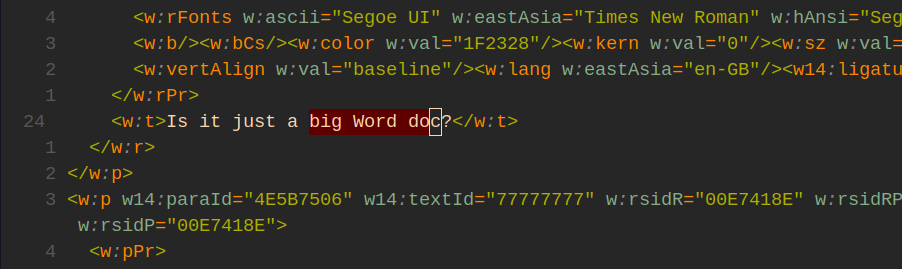

In Word, you only see the parts of the file that are for the end reader. If you open the same file on GitHub, you’ll be shown the entire file, including code contents.

It is worth going a bit deeper on how files are constructed. You can think of most computer files, including Word docs, as having three layers.

Presentation layer

First there’s the presentation layer. This is what you see in Word.

But how does Word know how to present this to you? Only because it is reading and processing literal instructions that were provided by code in the file that you opened. That code lives in the file alongside the English language text of the Word doc.

Every time you open a file in Word, it quickly reads the code parts of the file to understand the formatting instructions being given, and it selectively shows you just the English-language parts of the file, changing the size, shape, and color of the words as instructed.

By the way, the same thing happens when you visit a website. Working quickly in the background, your web browser downloads a file from the Internet and reads the code inside for rendering instructions. Then it paints your computer screen with the result of processing those instructions.

Source code layer

Below the presentation layer, there’s middle layer, where you can see the source code of the file as plain text.

Looking at this layer of a Word doc, you can see both your text in English and the code around it. When you open a file in GitHub (or any code viewer or editor), it shows you everything on this layer. It does not try to interpret the code as instructions like the Word app does, it just shows you everything in the file as plain text.

Both humans and computers can read and do things with the plain text layer of a file, as long as they’re given the right tools. This layer is represented in letters, numbers, and punctuation marks in both English and computer languages like HTML and Python. It has both the parts of the file that are “for computers” and “for people” together in one text-based medium.

How does this help you? It means there’s a chance that GitHub could be the home of text content you want to manage, and you can manage it if you learn to work around the code.

As a caveat, I should say it’s also possible the text content you want is not in GitHub but a separate database that is not actually version controlled. It depends on how the work is structured. Consult the tech person on your team.

As a second caveat, you will probably need some kind of separate access to a presentation layer for the same content, like a testing website if its a web project you’re working on. But if you have that, then you have what you need to work in GitHub.

With caveats out of the way, the main thing to remember about this layer is that everything here is just text. If you are used to working with text in Word, you can learn to be adept at working with code in GitHub.

Binary code layer

Finally there’s the lowest layer, binary code.

This is really only legible by computers. It does contain the parts of the file that are “for people,” but each letter has been translated into ones and zeros and then compressed into an alphanumeric shorthand for sequences of ones and zeros.

You don’t need to worry about the binary layer unless you’re Keanu Reeves, or a computer scientist.

Word actions compared to Git and GitHub actions

Folder: Repository

In a complicated Word-based project, there is often a folder for the project, with multiple Word files saved inside. They might be various drafts, or they might be pieces of a long manuscript like a book.

Git organizes files and folders the same way, only it also has the concept of a repository, which is a special, version-controlled folder that Git knows how to track and sync between different computers.

When people move code around, they do so by moving these repositories, because in computer code, files are heavily interdependent. A change in one could break how another works. So rather than send files in isolation, like you might with a Word doc, you send whole repositories of code.

People use GitHub because it makes sending folders of code a lot easier. In that way, GitHub is kind of like Google Drive or Dropbox or Microsoft OneDrive.

Save: Commit

After making a change, you “commit” it to save it.

The only difference is that you have to enter a little message with every commit / save. This might be annoying, but the idea is that after a while, if you need to go back through the version history, you can remember why you or someone else made that change. Kind of an interesting idea, right?

Different people have different norms around commit messages, but you can’t go wrong with an active verb and a phrase about what the change does:

Edited the About page

Fixed a broken link

One other weird thing about commits. In Word you can save each file independently, but in GitHub, you save the whole set of files that make up the repository. That’s because of the interdependence of files mentioned above. It feels a bit intense at first, but honestly it works out fine.

There are ways to save without committing, but they require code editors. See Clone: Download below.

Version: Branch

When you make a copy of a Word doc and then edit the copy, it becomes a separate version. If a co-author makes changes on another copy, then you have two versions you must reconcile.

Git branches are like that. Each person can make a branch, make changes on it, and then bring it back to the table to figure out how to merge it with any other branches.

Branches are distinguished by their names. People have different ways of naming branches, but they generally want just a few lowercase words connected by dashes, like this:

new-homepage-content

proofreading-user-guides

(Dashes are used instead of spaces because GitHub thinks of spaces as hard boundaries between things, and the branch name needs to be just one thing.)

Branches can be created on GitHub or on a downloaded version of the repository, using a code editor. See Download: Clone and Upload: Push below.

Branches have a key difference from Word workflows, in that they work across files, like commits.

In Word, you might control versions by creating copies of your file under different names, like “Article draft - version 6.docx”. Or you may even have folders for different versions of a big project. Or if you are using Google Docs, the version history can be managed for each Doc.

Git does not let you do any of these things. It can’t, because branches are made of chains of commits, and every commit is registered at the repository level, not just the file or folder level.

At first it felt odd to me that Git version control does not rely on file names. Then I realized it’s actually very economical. Then my whole paradigm shifted, and I could never look at a file name like “Article draft final 14 revised by Janet 6 July 13 final FINAL.docx” the same way again.

Email: Issue

In a Word-based workflow, there is no dedicated way to request that someone write something new. If there’s not already a draft to comment on, the request might just be directly communicated to the writer.

This is not organized enough for code projects, because requests for work can come in thick and fast. So GitHub borrows the concept of an IT support ticket to make an organized way to log requests for future work. These tickets are called issues, and they are helpfully numbered and stored next to the repository on GitHub.

Each issue requires a name and description in addition to a number. It is not always directly linked to the related code, but it might cite code passages or just explain what the problem or request is.

Issues provide a shared record of work to be done by the members of a team. Developers often keep issues in lists and use them to plan coding sprints, and then they “close” them when they merge edits that address the issue.

If you see a number, often with a hash, somewhere in GitHub, it is often a link to an issue. You might see it in a commit message:

Put mission statement on the home page #751

Or in the name of a branch:

b-751-mission-statement

People do this to provide context when working between many different files and conversation threads, especially on large projects. GitHub helpfully turns these hashed numbers into hyperlinks, allowing anyone to follow the context trail even much later.

Attachment: Pull request

When you finish a piece of work in a Word doc, you might send it to your collaborator via email, or you might just let them know that you’ve finished your bit in a shared online doc and you’re ready for them to look at it.

In GitHub you can open a pull request to ask someone to look at something. GitHub will need to know which two branches should be compared. Usually these are the main branch in the repository, and your branch with the new commits.

In addition to the actual edits or changes, pull requests take a name and a description. You can often leave the description empty if everything is explained in a linked issue. People often link to issues with “fixes” or “closes”, like this:

Closes #751

This tells GitHub that if and when the changes are accepted, then issue 751 should be automatically “closed” or marked complete.

Tracked change: Diff

When you’re opening a pull request, GitHub will run a scan and show all the differences or “diffs” between your branch and the main branch.

Think of this like the bramble of red tracked changes that grows down the right-hand margin of a contentious manuscript in Word.

The diff mechanism in GitHub is extremely robust. In fact, in a manner of speaking, you can’t turn off tracked changes in GitHub. The whole system is designed to enforce scrupulous tracking of every change made, permanently. Anyone who has access to the repository can go back and view the entire history—every single commit.

(Okay, there is a way to “ignore” files, by adding the filename to a special text file named .gitignore. But it’s not possible for edits to files that Git tracks.)

I found this a bit scary in the beginning. What if someone goes back and judges your edits, years later? They can. They might.

But look on the bright side. The practical, efficient, blindingly well-lit side. If somebody finds a problem, they can click a few things and see exactly when and ideally why someone changed the offending code, even years later. This makes it possible to fine-tune a project over time, with consistency, clarity, and precision.

Review: Review

This one is the same in both worlds!

If you are reviewing a Word doc, you might use margin comments, tracked changes, and maybe a list of notes.

In GitHub, code reviews serve that function, with a few differences.

During a review, you can comment on the diffs you see, and at the bottom you will be asked to type an overall comment and approve the changes or request further changes.

It’s less common to add your own edits at this stage, but you can if you want, by adding more commits to the same branch. The pull request will be automatically expanded to include your commits in its scope.

Accept all changes: Merge

In Word, there comes a time when you’ve looked over all the tracked changes and you’re ready to accept them all, creating a clean copy.

This stage is reached in GitHub when all consulted parties have given their “Accept” approval to the pull request using the review feature.

The process of accepting a branch is called merging. It effectively takes all the commits from the proposed branch and stacks them on top of the main branch, lengthening it.

Conflicts sometimes arise at this stage, and they are tricky to unravel. If that happens, ask a friend with deeper Git knowledge for help.

Save as: Fork

You can save your own version of someone’s repository by “forking” it. You’ll get the same exact code in your version, and a full history of all the branches and commits too.

On GitHub, the fork will then be associated with your username, rather than the user or organization that owns the original repository.

Forks can be quite a flexible way to work on your own version but also benefit from changes made in the original repository. If someone changes the original by adding more commits, you can choose whether to bring each of those changes into your version.

The caveat is that they can lead to more conflicts, if a lot of time passes between syncing the fork and the original repository.

You can open a pull request from a fork just like you can from a branch, which as you recall is like a named version of a folder. Just make sure you select the right target branch. Usually the target will be the original repository’s main branch.

Not sure whether to open a branch or create a fork?

- Go for a branch if you’re given the option. The main authors of the repository might have put you on a team that has some editing privileges, and it will be cleaner if you just put a branch inside their repository. Ask for access if you think it’s likely you will get it.

- If you have no access, create a fork.

Download: Clone

The first time I was asked to contribute to a public repository, I clutched my introvert pearls in horror. I felt my desk was about to be dragged onto a stage in front of a bunch of people, who would then sit there watching me write. So much pressure!

But most programmers do not edit directly on GitHub. Using Git, they download the repository to their computer, work on it in private, and then upload their changes back to GitHub.

Recall that Git and GitHub are separate things. Git is the underlying version control system. It’s open source and interoperable on different kinds of computers and code editing apps.

In that way it’s kind of like the DOCX file format itself. You can open a DOCX file in Word on a Windows computer, Word or Pages on a Mac, Google Docs on the web, and more. Similarly, you can open a Git repository on GitHub or on your own computer’s file explorer, or in a code editor like VS Code.

Downloading is called “cloning” in Git lingo. If you want to do this, choose and install a code editor, and follow the cloning instructions provided by the editor you use. Most often they will involve copying and pasting a URL that ends with “.git” into the right place in your editor. You can always find the clone URL on the repository’s main GitHub page.

You might be tempted to use the “Download ZIP” or “Download raw file” buttons on GitHub, but that will be harder in the long run if you want to edit anything and send your changes to someone else. The part of Git that helps you send code will get separated from the project files, and you won’t be able to re-attach it without expert help.

Sync: Pull

The latest versions of Word can automatically sync documents across computers, if the document is shared by multiple people.

Git can sync things too, but only on your explicit instruction. You remain in direct control of the branches and versions at all times.

The command for syncing down from the cloud is called pull. Each pull action only affects the current branch. If you have made local changes, Git will require advanced instructions on how to combine them with remote changes.

Upload: Push

Word files that have been edited offline can be uploaded to shared locations, obviously, but then you have to figure out how to combine them with existing versions, or at least how to communicate to other people that your version is the latest one.

Uploading with Git is called pushing.

If no one else changed the branch since you pulled it, then you can push your changes quite easily. The commits will simply be stacked onto the end, for everyone else to see.

But programmers usually go one further. They create a new branch on their computer, add their changes as commits, and finally push that new branch to GitHub. As long as no one else used the same branch name, everything goes smoothly. They can then open a pull request for that branch, view diffs, receive reviews, and finally merge their work into the main branch.

Undo: Commit

What! How can undo just be a commit?

Bear with me. I recognize that the undo and redo buttons are extremely important in Word.

Brace yourself: in Git land these are kind of dirty words. The idea with GitHub is that everything is tracked, even mistakes. Computer bugs can be so hard to find that every bit of information about how something went wrong might be helpful at some point.

Many programmers embrace mistakes as inevitable, because computers are such unforgiving readers. If you make a mistake in a repository, remember that you are not the first or the last.

To undo something after you’ve already committed it, you just need to make the change in reverse and record it as another commit. Yes, it looks silly. It’s normal.

There are fancier ways to truly undo things, like reset, but they are not beginner-friendly. For now, just add another commit.

A precise instrument

When I first started programming, I remember feeling that I was losing precision in manipulating text. They had us write programs at the University of Michigan that formed sentences from sequences of letters, or searched text for particular sequences of letters.

I had the perception that code was a blunt instrument when it came to text, that I could not possibly write a program to fine tune text in the way I could by writing and editing it directly.

I was very, very wrong. The perception I had was just a beginner’s fog. It was like the hesitancy many language learners feel in pronouncing new words in the language, because they do not yet trust the words will work, that others will understand their meaning.

Well, the words of Git do work. Git is an incredibly precise and flexible tool for working in very complex ways, with high levels of collaboration, over long time periods, with very large amounts of text.

This is because code is just text. In creating a distributed version-control system for code, the makers of Git made a gleaming digital file cabinet ready for reams of documents in human languages to be neatly held, distributed, edited, and supplemented.

It’s like when curb ramps started to be installed so wheelchair users could cross the street more easily, and nearly everybody benefited.

Except, to be fair, the Git learning curve is steeper than most curb ramps.